By Hannah Chinn

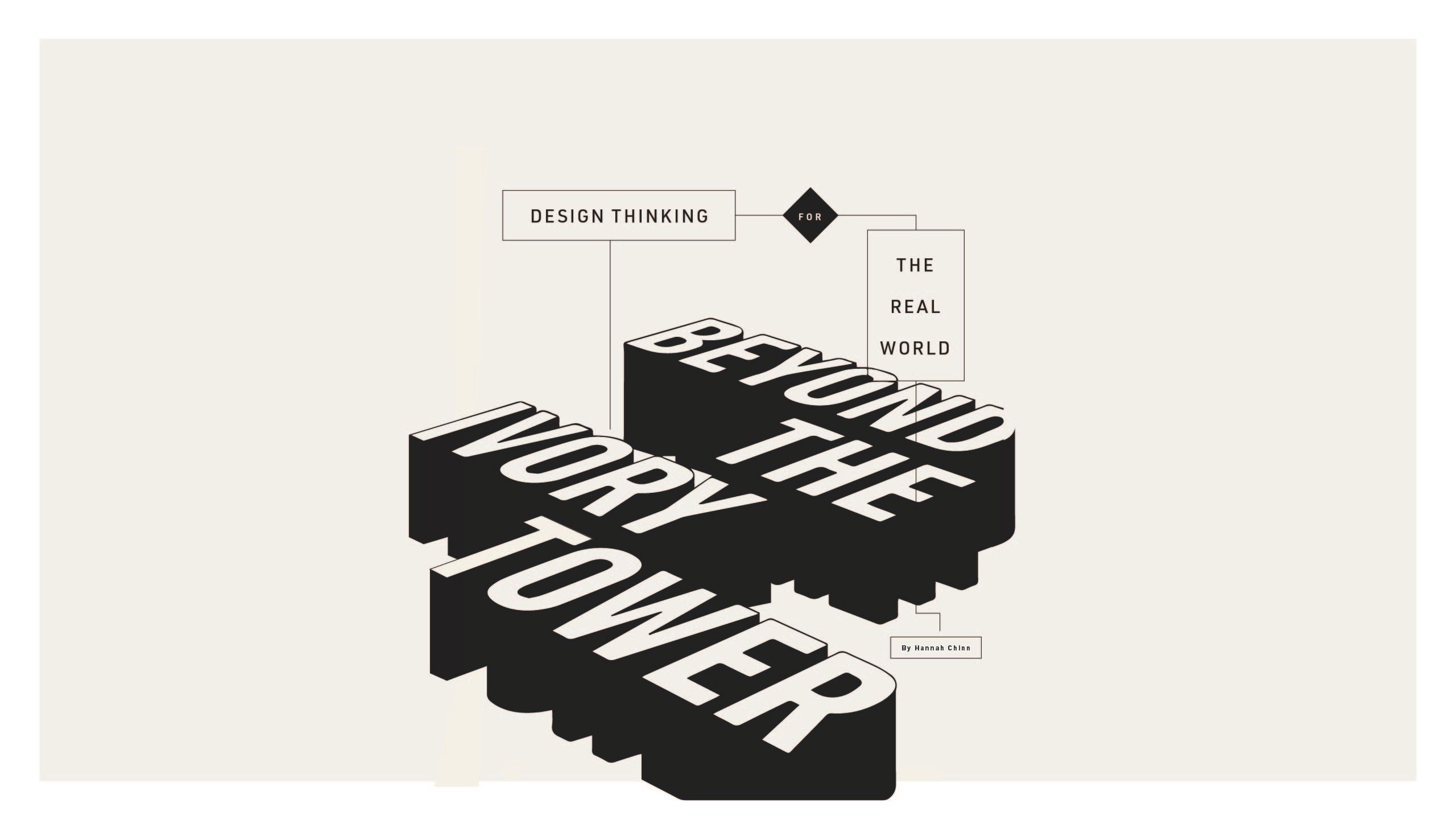

As times change, so does the curriculum at the Temple University College of Engineering. With guidance from alumni and faculty, the college’s Senior Design capstone is evolving to strengthen creative capabilities, foster industry connections, and better prepare its next generation of young engineers for a world in constant flux.

At the heart of it, says Temple Engineering alum and Board of Visitors member Joe McGinley, “Engineering is about identifying a need and problem-solving.”

It’s not just math or science or technology, he adds, although those are necessary components. Instead, it’s about identifying an issue, asking the right questions, and developing a solution. “Beginning with even early design projects as a freshman, working from identifying the issue, problem-solving and thinking [critically] about projects are really key.”

Nowhere is problem-solving more valuable than in the Senior Design capstone. Like all accredited engineering schools in the United States, Temple’s College of Engineering must meet seven student outcomes, including communication, teamwork, and leadership—and requires a final capstone project that encompasses them all. At Temple, that project is a year-long course of independent work, supervised by a designated faculty advisor and culminating in a final team presentation.

For Tom Edwards, chair of the Department of Engineering, Technology and Management, the project’s primary goal is not product-oriented. Instead, the Senior Design capstone tasks students to harness all the skills they’ve acquired as underclassmen and take them one step further through what engineers call “design thinking.” “In the real world,” Edwards says, “You don’t get textbook problems.”

Design thinking is the practice of asking questions and thinking both critically and creatively. It’s what helps engineering students leave the nest of hypotheticals and enter into a world that requires palpable, lasting solutions. For Temple alums like Salman Alotaibi and Nuo Ivy Chen, design thinking has already inspired innovation.

For mechanical engineer and inventor, Salman Alotaibi, an introduction to design thinking came while tinkering with gadgets alongside classmates and friends. His later Senior Design capstone would be informed by life: After a backpacking trip through the United Kingdom one summer, Alotaibi designed the award-winning Pure Trip, a lightweight, portable washing machine meant for hikers and travelers.

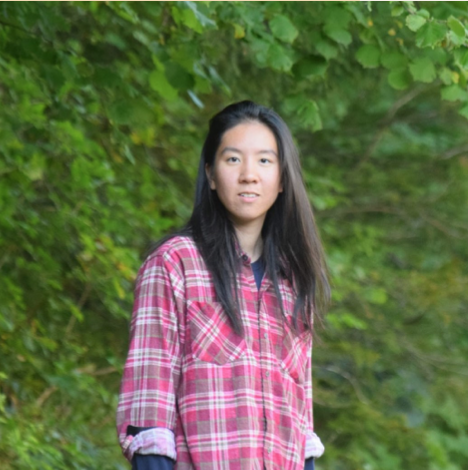

For recent grad Nuo Ivy Chen, design thinking came sophomore year, when she put the abstract principles of heat and mass into practice by designing a heat sink. “[Design thinking] forces you to put on another hat,” says Chen, who double majored in German and is now setting her post-grad sights on work abroad. “It’s not just solving an equation from a book—it’s like another step.”

Salman Alotaibi

Salman Alotaibi

Ivy Nuo Chen

Ivy Nuo Chen

It follows, then, that Senior Design requires some design thinking of its own. The College of Engineering is always striving to evolve its curriculum and capstone project to better prepare students for what’s next. “[The project] is important because it gives students a chance to practice everything they’ve learned,” says David Brookstein, mechanical engineering professor and senior associate dean of the undergraduate program. “What we’d like to do is connect that with industry, with outside organizations that have projects [for] students to do.”

In Temple’s current model, students build proposals and projects while reporting to a departmental coordinator who, in turn, works with the lead faculty member for the duration of the endeavor. In the evolving model, that lead faculty member would be accompanied by a program director, someone with industry connections and experience who engages outside sponsors —from for-profit manufacturing companies to government engineering divisions—to support students in their work.

Incorporating industry sponsors is not an untested concept; many universities and engineering programs have pursued similar programs. But Temple, situated at the cross-section of Philadelphia’s burgeoning medical, energy, and manufacturing industries, is in a unique position to place students where the action happens. Brookstein says, “It makes sense to be more outward-facing. We want to be less of an ivory tower, and more of a partner with industry.” Tom Edwards agrees: “I think everyone involved with Senior Design understands that the more it mirrors an industrial project, the better experience it is for the students.”

So, what does that look like in practice? The program’s first connection points are local companies, like Ben Franklin Tech Partners or the Delaware Valley Industrial Resource Center, where Temple students have already flourished as interns or been hired as recent graduates. These companies challenge student engineers to solve everyday issues, giving them a running start on their careers and a competitive edge when they graduate.

“It makes sense to be more outward-facing. We want to be less of an ivory tower, and more of a partner with industry.

As both a Temple alum and a current engineer, McGinley sees benefits of this model even beyond its impact on students. “It’s a win win win: A win for industry, a win for students, and a win for the college,” he says. Fostering sustained partnerships between universities and local industry can lead to new kinds of collaboration and synergy, a spectrum in which students and professionals work to benefit each other and the world. This vision dovetails with Temple’s commitment to growing professional relationships and career connections internationally. Temple University has classrooms and facilities in Japan and Italy, meanwhile Nuo Ivy Chen, for instance, is using her Temple education as a launchpad to pursue a Fulbright scholarship in Germany.

In the near future, McGinley imagines this new model taking shape as a series of multi-year design projects conducted by teams of upperclassmen, underclassmen, and faculty members. He describes this as the integration, rather than the displacement, of core concepts in engineering coursework. He says, “If you’re engaged in a project on day one, you can see how didactic lectures fit into the real world. [You can] see why it’s relevant.”

The college hopes to begin implementing the new program in the Fall of 2021, having been stalled by the COVID-19 pandemic, which poses a relevant question:

In a world turned upside down by the events of 2020, what will be required of engineers in the future? To the faculty and alumni of Temple’s College of Engineering, uncertainty brings purpose to the field. The growing threat of climate change, a global pandemic, and even political unrest can all benefit from the practice of design thinking.

“All problems can be worked through and solved [with logic],” McGinley says. “You just have to understand what the goals are and define the problem.” Because engineering, at its heart, is about solving problems. And the world could always use more problem-solvers.

Graduate Profiles

Nuo Ivy Chen (’20)

Nuo Ivy Chen was introduced to the field of engineering when she joined her high school robotics team. But even once she got to college, she says, she wasn’t 100% sure. Engineering is a rigorous field, which means retention can be difficult. For Chen, both professional associations like the Society of Women Engineers and informal mentorship by older Temple students kept her moving forward. Without it, she says, “I would’ve had a very narrow view of what I could do or what I was capable of.”

Chen was a remote intern at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab this summer, and enrolled in classes at Carnegie Mellon for the fall; she’s also the recipient of a Fulbright scholarship, which she’s planning to use to engage in research in Germany this winter. After that? “We’ll see what happens,” she says. “Right now, I want to just learn more.”

Chen, second from left

Chen, second from left

Salman Alotaibi (’19)

Growing up in Kuwait, Salman Alotaibi would take apart his toys, curious about the motors or moving parts inside and convinced he could find out how they worked. It got so bad, he says, that his father gave up on buying him toys—instead, Alotaibi was sent to an after-school science club where mechanical engineering would become his passion. He designed his first invention at 15 and took out his first patent at 17.

He traveled to the States in 2014 to study English, then applied to Temple’s engineering program. “At [Temple], I had colleagues and classmates,” he says. “Everyone shares, everyone tells you about their work; [and] we help each other to develop ideas, whether on or off the campus.” Following graduation, Alotaibi spent most of the last year working for Schlumberger in Colorado. Now, he’s back in Kuwait preparing for a masters’ degree program in Design Engineering in Italy. At both school and work, he’s proud to be “Temple made.”

Joseph C. McGinley, M.D., Ph.D. (’96, ’97, ’04)

Most university alumni graduate with one Temple degree. Joe McGinley has four.

Combine his bachelors’ and masters’ degrees in mechanical engineering with his M.D., plus a PhD in physiology and it makes for a total twelve years of Temple schooling—plus one additional year of interning at a Temple-affiliated hospital. “Obviously, I was committed to Temple very early on,” McGinley laughs, adding, “A lot of my success today is based on that grit and problem-solving experience I received at Temple.”

He’s a physician, engineer, and entrepreneur as well as the founder and CEO of McGinley Orthopedics and President of McGinley Manufacturing. He’s also a heavily involved alumnus as a member of the College of Engineering’s Board of Visitors, Chair of the Senior Design Project committee and member of the Temple University Leadership Council.